This is Part 2 of a two-part article. Part 1 addressed the family-affiliated defendents linked to January 6 extremists groups.

One can delineate potent police counterterror efforts and countermeasures focused on family-affiliated extremism between those activities effectuated internally to the police department and those focused on the public. Attention to these distinct responses can prove helpful when management crafts steps to undermine radicalism in the United States. Subsequently, law enforcement’s experience with January 6 extremism and the investigation of criminal conduct by rioters that day are addressed.

Police Countermeasures Internal to the Department

Foremost and foundationally, police management must recognize that terrorism merits organizational concern. The administration should allocate personnel and other resources to undermine radicalism. Also, management should raise awareness of the threat and its negative implications for “police officers and the community. Acknowledgment that common crimes can be associated with extremism” should buttress police awareness of radicals in their jurisdictions.

Threats to officer safety stemming from these nontraditional criminals must be emphasized with personnel. Attacks on officers “by terrorists of varied ideological affiliations encompass spontaneous and pre-planned incidents across varied means of attack” (e.g., gunfire, vehicle, and edged weapons) in diverse settings (e.g., while on the street, in a vehicle, and at a precinct). In May 2020, for example, Boogaloo member Steven Carrillo shot and killed a Federal Protective Service officer in Oakland, California. The following month, Carrillo killed a sheriff’s deputy in Santa Cruz, California. Subsequently, he was later captured and faces federal and state charges surrounding these deaths and other counts. Also, risk to police arises while countering a kinetic “incident by a sovereign citizen, militia member, hate-affiliated operative, a jihadist, or another culprit.”

“Multiple state statutes can be engaged to prosecute persons suspected of extremism. This is so even as federal prosecutions are often the mainstay of terrorism cases. Both federal and state laws may have applicability relative to an accused terrorist or” hate-crime perpetrator, among others. The following criminal activities may have relevance “in prosecuting radicals: terrorism, sedition, gang membership, organized crime, hate crimes, arson, possession of unregistered explosives, and stalking. As sometimes such fanatics are involved in precursor crimes or other criminality, their unlawful actions may” also include money laundering, weapons or drug offenses, fraud, extortion, identity theft, human trafficking/smuggling, and sex crimes.

It is critical for police agencies to “use existing federal, regional, state, local, and tribal counterterrorism organizations and resources in their efforts to subvert terrorism locally. For instance, over 100 Joint Terrorism Task Forces, some 80 regional and state fusion centers, multiple drug and other specialized task forces, as well as anti-money laundering and” counterterror finance groups, should be engaged as relevant. Likewise, the use of classified and nonclassified “intelligence databases, along with submission to and accessing national suspicious activity reports and suspicious transaction reports (via the Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network), are [utile instruments.] Of note, the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database contains information about known or suspected terrorists. Daily some 55 traffic stops that get an NCIC hit on a suspected terrorist, meriting appropriate follow-up by police.”

Obstacles to police department success in taking steps internally to undermine extremism are manifold but may rest on faulty assumptions, inaction, or other circumstances. “Some departments are of the incorrect mindset that extremist threats will never happen in their town. The lack of kinetic attacks, reported hate crimes, and silent terror fundraising and money laundering efforts are not indicative of the lack of radicalism in one’s community. Other jurisdictions may project terrorism as a concern nationally but not so locally.”

“Along with such thinking is the belief that while an acquaintance has characteristics otherwise meriting concern, the person is perceived as innocuous. Elsewhere, a suspect may engender the modes of radicalization, indicators of mobilization, and other attributes of extremism that are unrecognized. Preconceived perspectives of who might be a radical – even stereotyping – may cause wrong determinations, such as false negatives and positives. Still, a police department may face multiple” pressing challenges to their limited resources straining their ability to monitor and counter rising “extremism. In that setting, the issue is not a lack an awareness of the threat but a capacity to assuage it.”

Police Responses Centered on the Public

Police departments may craft multiple, distinct counterterrorism efforts that center on the public. They should fixate on endeavors that detect and counter radicalization and terror recruitment efforts. Police should become “skilled at ferreting out individuals who have become mobilized (radicalized persons who support the use of violence in their efforts and intend to do so). Although not foolproof, it is imperative that criminal analysts assess questionable behaviors that are dangerous” independently of other considerations (e.g., declaring one is seeking martyrdom) and warrant immediate countermeasures (e.g., impending travel to a conflict zone).

“Paying attention to the prospect of family terror network-centered suspects is worthwhile, as this type of terrorism has become prominent globally. By understanding the influences of families on the creation of terrorists, incapacitating the likelihood of their involvement in terrorism is enhanced. Multiple family members have taken part in prominent U.S. extremist incidents,” for example:

- 2010 killing of two police officers during a traffic stop in Arkansas by the father and son (Kanes; son did the shooting at the father’s behest);

- 2013 Boston Marathon attacks by Tsarnaev brothers;

- 2014 assassination of two Las Vegas police officers by husband and wife (Millers); and

- 2015 San Bernardino shooting (spouses Farook/Malik).

“Other successful countermeasures include pursuing traditional policing efforts like conducting traffic stops and responding to calls for service. These bread-and-butter policing functions should be carried out against a cognizance of well-known signs of terrorism: surveillance of and eliciting about a target, testing the security of an asset, acquiring supplies, fundraising, impersonation, conducting a dry run, and getting into position for an attack. Using informants and undercover agents in building a case has relevancy as in other investigations. Informants and undercover agents are used in many extremist cases across all ideological spheres. In [the fall of] 2020, an undercover FBI employee posed as a member of Hamas while interacting with two anti-government operatives (Boogaloo Bois) in relation to the latter offering themselves as mercenaries” for Hamas, a designated Foreign Terrorist Organization. “The pair were accused of conspiring to provide material support to Hamas.”

Police can leverage technologies “in their quest to combat terrorism. For example, they can monitor social media, use commercial and proprietary monitoring tools, and get search warrants for electronic devices, including phones and computers. Also, license plate readers, stingrays, infrared cameras, and explosive and metal detectors are among those technologies that can aid in disrupting radicalism. Still, terrorists are skillful at diverse technologies to communicate, conduct” command-and-control “measures, and raise funds. Heightened capabilities with encryption and emerging technological developments often force authorities to play catch up. The lack of cooperation by some companies in certain instances makes accessibility to terrorist data – even once a warrant has been issued – quite difficult.” Also, the insufficient training on social media technology within agencies and limited human resources for specialization make the necessary cooperation all the more complicated.

Next, efforts should be centered “on preventing the acquisition of extremist funding and other material support, such as the provision of weapons, safe houses, fake” identifications, training, and expert advice. Besides undermining fundraising, focus needs to be paid to “the movement of these monies and interdicting money laundering efforts (when monies derive from illicit actions). Consideration should also rest on stopping the next strike. It is imperative to initiate risk and vulnerability assessments so that damage from attack is limited. Such security assessments examine the assets requiring protection, their vulnerability, and criticality. It is paramount for jurisdictions to generate a list of the most prone government, private sector, nonprofit, and nongovernmental organization targets and encourage them to harden their sites.”

Several variables are relevant when responding to a terrorist attack. Initially, one must weigh the form of attack the police may face: bombing, active shooter, vehicle attack, a combination of them, or others. Upon arriving at the location, police must detain or otherwise neutralize the perpetrator(s). Terror incidents may not prove static as an active shooter situation can evolve into a hostage scenario, the converse, or multiple attacks at disparate locations. New York Police Department’s Critical Response Command has heeded this concern by training its members to detect and impede attacks such as chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, explosives, and the like.

The police department “should encourage the public’s involvement in combating terrorism. The public can recognize the signs of terrorism, inform police of their concern, and aid them in preventing attacks. In particular, [the] industry can facilitate identifying suspicious behaviors, transactions, and persons (employees and customers) that have a nexus with terrorism. Likewise, sustained, trust-infused, and impactful community policing efforts have a role in undermining and uncovering extremism, especially in otherwise alienated and marginalized populations. Fostering engagements with well-known, credible community leaders can contribute to increasing public vigilance and resilience to infiltration by radicals. Neighborhood policing can help develop sources, gain insights [into] suspicious persons and activities, and pinpoint where to use informants and undercover agents in future sting operations.”

High-profile “involvement in communities can deter hate crimes and other extremism in the area, including through de-radicalization efforts. Additionally, once police cement ties with a neighborhood, they can build up bonds with particular households. In doing so, police can detect a family terror cell, encourage activities within the family to expunge radicalism that may exist, or prevent infiltration of extremism within a home.”

Law Enforcement and January 6

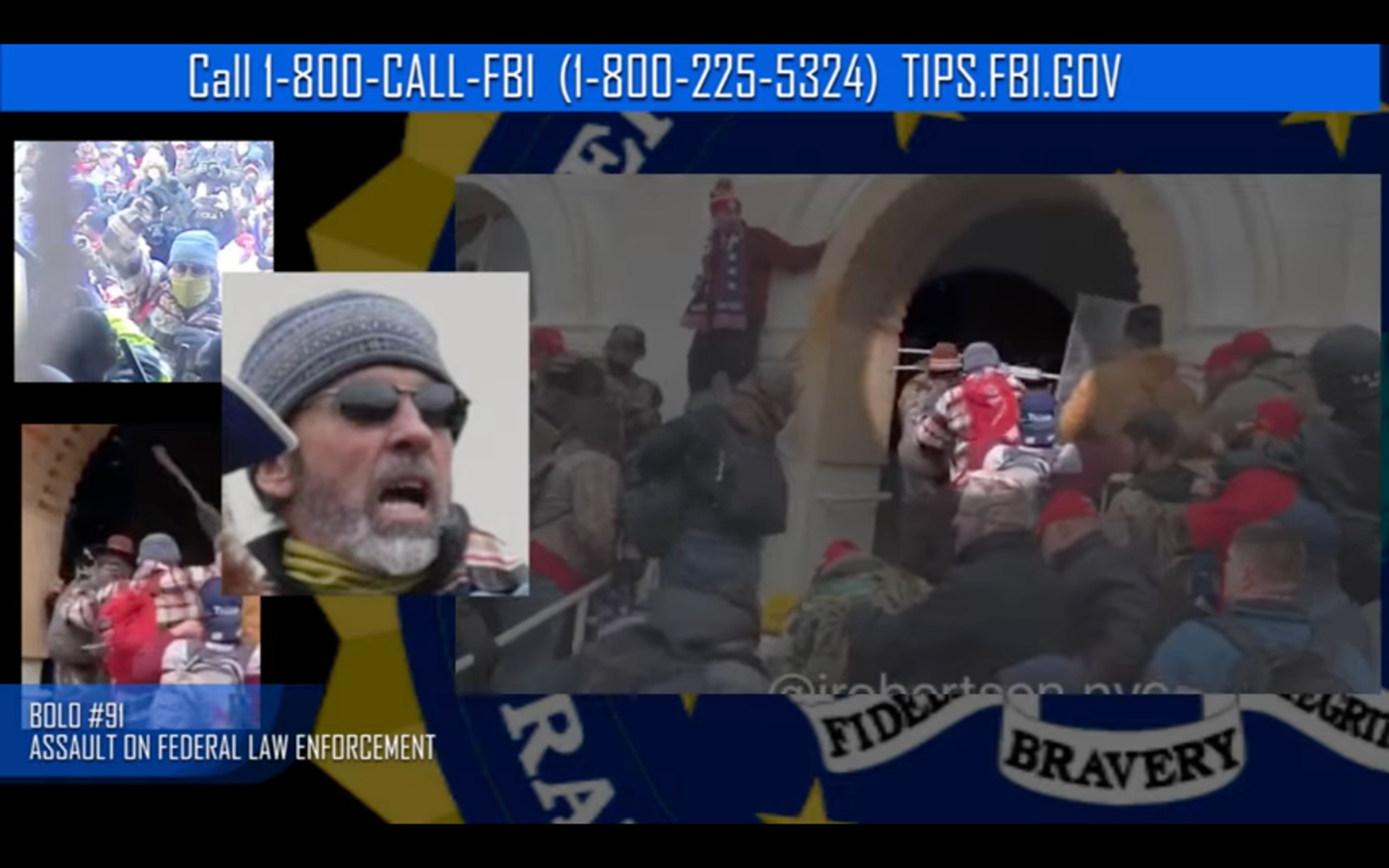

Law enforcement identified U.S. Capitol breach suspects from various sources, such as tipsters, coworkers, friends, (other) family members, informants, social media accounts of suspects and their incriminating remarks or poses on videos and photos, news media stories, cell site records, interviews with suspects and others, video surveillance footage, and revelations arising from execution of search warrants. Distinctive clothing (“camouflaged-combat attire”), headgear (baseball caps to tactical helmets affixed with stickers), goggles, group patches/logos/insignia, backpacks, a Confederate Battle Flag, and prominent tattoos aided in their discovery during preliminary investigations. Other evidence has been garnered through troves of cached Parler (“conservative alternative to Twitter and Facebook”) accounts and insights from communications on Telegram channels.

Law enforcement responses to the Capitol Hill siege on January 6 represented a watershed point in the challenge of domestic extremism threatening the peaceful transfer of political power. Law enforcement authorities had the enormous challenge of restoring order and defending the seat of American democracy as the world watched in shock. The incident showed flaws in intelligence gathering, communication, training, readiness, management, and political calculations, among other failings. More broadly, the June 2021 U.S. Senate bipartisan report, “Examining the U.S. Capitol Attack: A Review of the Security, Planning, and Response Failures on January 6,” (Report) found:

- The federal intelligence community – led by FBI and DHS – did “not issue a threat assessment warning of potential violence targeting the Capitol on January 6.” FBI denies this allegation, and they claim that prior to the U.S. Capitol riot, they provided a cautionary alert concerning the potential for violence.

- USCP’s [U.S. Capitol Police] intelligence components failed to convey the full scope of threat information they possessed.

- USCP was not adequately prepared to prevent or respond to the January 6 security threats, which contributed to the breach of the Capitol.

- Opaque processes and a lack of emergency authority delayed requests for National Guard assistance.

- The intelligence failures, coupled with the Capitol Police Board’s failure to request National Guard assistance prior to January 6, meant District of Columbia National Guard was not activated, staged, and prepared to quickly respond to an attack on the Capitol. As the attack unfolded, DOD required time to approve the request and gather, equip, and instruct its personnel on the mission, which resulted in additional delays.

The report also published 21 findings of facts showing there were multiple deficiencies across various agencies and departments that contributed to the security, planning, and response failures on January 6. Among crucial lessons from the Capitol breach incident are for law enforcement to elevate communication, coordination, training, staffing, and intelligence sharing capabilities and expand security funding. Additionally, there is a need to reassess the existing security standards. In addition, law enforcement personnel also displayed incredible bravery and perseverance while significantly outnumbered on January 6 in the face of hours-long onslaughts by rioters, as of June 2023, 109 of whom are accused of using “a deadly or dangerous weapon or causing serious bodily injury to an officer.” Hopefully, this study shows the need for law enforcement and the intelligence community to consider family-affiliated extremism as an enduring feature in 21st-century terror threats.

Conclusion

The 90 kin-connected prosecutions representing 177 persons involved in extremist activity on January 6 demonstrates the importance and ubiquity of family-affiliated extremism worldwide. The reality that 17.1% (177/1,033) of the people prosecuted in the siege at the U.S. Capitol participated in the onslaughts with other family members epitomizes the dangers of radicalization within a family unit. Also, the existence of family terror networks across ideologies was confirmed in 281 individuals in the 2019 book Family Terror Networks. While the impetus for a person becoming an extremist can be multi-dimensional, family relationships are not the sole factor affecting radicalization. Still, given its frequency globally and so prominently on January 6, this terror phenomenon merits closer attention.

Law enforcement’s broad efforts in combating terrorism will concurrently undermine a subset of this political violence, namely, family-affiliated extremism. This is especially so once law enforcement fully appreciates the pervasiveness and negative effects of family terrorism networks. Police efforts in combating terrorism need to be at the forefront of their activities. After all, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s May 24, 2023, National Terrorism Advisory System projected:

In the coming months, factors that could mobilize individuals to commit violence include their perceptions of the 2024 general election cycle and legislative or judicial decisions pertaining to sociopolitical issues. Likely targets of potential violence include U.S. critical infrastructure, faith-based institutions, individuals or events associated with the LGBTQIA+ community, schools, racial and ethnic minorities, and government facilities and personnel, including law enforcement.

Against this backdrop, it is probable that extremist activity in the United States will continue to be prevalent in 2023 and beyond, represented, at times, by participants whose radicalization has emerged within a family unit, and whose mobilization to violence occurs in unison with other family members. Indeed, these scenarios were seen on January 6 and in numerous instances beforehand in the United States and abroad. In the face of such foreboding political violence, U.S. federal district judge Amit Mehta aptly stated during the May 2023 sentencing of Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes, “What we absolutely cannot have is a group of citizens who – because they did not like the outcome of an election, who did not believe the law was followed as it should be – foment revolution.” This is true whether the person acts as such alone or in concert with others, irrespective if they are kin or otherwise, particularly in presidential elections.

Retrospectively, January 6 was a watershed moment for law enforcement and the country. Some sought to explain this phenomenon through the lens of contagion theory, while others preferred non-theoretical explanations for the violence. What was witnessed that day was not “sightseeing” by pacific actors, but rather, violently inclined individuals who wreaked havoc on the country’s institutions and processes. Today, the irrefutable January 6 belligerency is characterized by some (e.g., particular politicians and media figures) as meritorious, patriotic actions. Such a perspective is wrong and undermines the foundations of democracy. Instead, the threat or use of political violence by anyone – irrespective of one’s political viewpoint or grievance – should be viewed as untenable. Otherwise, prospectively, political power will be transferred chaotically, led by individuals blinded by the aphorism “might is right.”

Dean C. Alexander

Dean C. Alexander JD, LLM, is the director of the Homeland Security Research Program and professor of Homeland Security at the School of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration at Western Illinois University. In addition to numerous peer-reviewed publications, he has authored several books on terrorism, including: Family Terror Networks (2019); The Islamic State: Combating the Caliphate Without Borders (Lexington, 2015); Business Confronts Terrorism: Risks and Responses (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004); and Terrorism and Business: The Impact of September 11, 2001 (Transnational, 2002). In addition, he is frequently interviewed by domestic and international media, such as the Washington Post, Boston Globe, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Chicago Tribune, Dallas Morning News, Orlando Sentinel, Associated Press, Voice of America, Security Management, El Mercurio, Tribune de Genève, and NHK. He has provided on-air commentary for television and radio stations, including CBS Radio, Voice of America, Wisconsin Public Radio, and CB-Business.

- Dean C. Alexanderhttps://www.domprep.com/author/dean-c-alexander

- Dean C. Alexanderhttps://www.domprep.com/author/dean-c-alexander

- Dean C. Alexanderhttps://www.domprep.com/author/dean-c-alexander

- Dean C. Alexanderhttps://www.domprep.com/author/dean-c-alexander

Huseyin Cinoglu

Dr. Huseyin Cinogluis anassociateprofessor of Criminal Justice in the Department of Social Sciences at Texas A&M International University (TAMIU). Dr.Cinoglupublished and presented extensively in the areas of (countering) violent extremism, (countering) terrorism, (de)radicalization, immigration, crime and criminality, identity formation, and terrorist identity formation. He authored or co-authored several books. His publications appeared in respected journals such as International Journal on Criminology, European Scientific Journal (ESJ), International Journal of Human Sciences, and IOS Press. Dr.Cinoglu wasinterviewedby Newsweek and Laredo Morning Times.huseyin.cinoglu@tamiu.edu.

- Huseyin Cinogluhttps://www.domprep.com/author/huseyin-cinoglu

- Huseyin Cinogluhttps://www.domprep.com/author/huseyin-cinoglu

- Huseyin Cinogluhttps://www.domprep.com/author/huseyin-cinoglu