Public engagement and participation involve community members in problem-solving, decision-making, and policy development. Partnerships provide actionable opportunities for key stakeholders to participate in decisions that affect their communities. In the emergency context, these partnerships concentrate on organized efforts and activities to prepare for, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of disasters or emergencies. Result-centered community partner engagement approaches can help protect people from many adverse impacts of emergencies by:

- Building community partnerships for response and recovery;

- Seeking and providing feedback;

- Offering training, drills, and exercises; and

- Applying lessons.

Advisory groups – members, sponsors, or those who staff or are considering joining them – should use this content for self-reflection and self-accountability. This article offers ideas regarding how to:

- Strengthen and operationalize tasks mutually beneficial to the government and community partners;

- Understand how to use actionable basics, including clarity regarding objectives, trust, transparency, feedback, support roles, just-in-time training, sustaining efforts, measuring success; and

- Provide additional resources.

Like any “use by” label or operating system update on a mobile phone, agencies and organizations must keep learning because knowledge is perishable. New information, laws, technologies, values, products, and services can limit the shelf life of expertise. However, lifelong learners understand that new lessons are constantly evolving and that what they know and do is a work in progress. Here are seven common beliefs and practices that can be modernized to increase result-centered engagement.

1. Return on Investment

For various reasons, some people believe there is little return on investment when involving community partners. Perhaps it seems like too much work or that the community partners get in the way of a government-centric approach or raise legal liabilities. This calls for new beliefs and practices.

Impact focused on public engagement with community partners moves beyond checking the box “Yes, we have an advisory committee.” Large disaster disruptions can overwhelm affected governments as they cope with constrained resources and strive to meet emergency services challenges. When adequately prepared, community partners with critical planning, response, and recovery capacity roles can reach and help more people than the government alone to prevent deaths and injuries.

Community partners should establish measurable goals and effective efforts to identify and close gaps between known emergency preparedness and response needs and capabilities. Taking responsibility for increasing capacities, competencies, and ongoing improvement are team activities, not those of a single department.

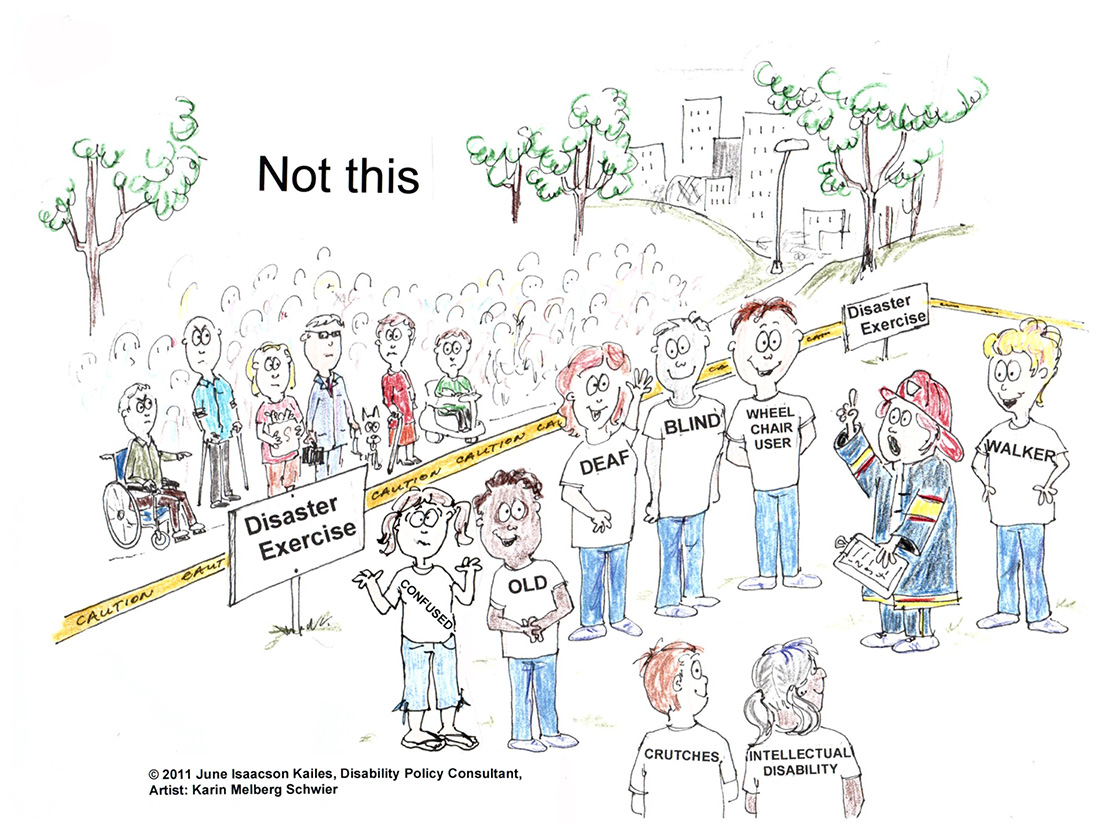

Planning partners must consider complex demographic shifts to include and represent the perspectives of aging, culturally and linguistically diverse populations. Doing so can help create policies, programs, and response capacity that include and benefit even the most disproportionately impacted groups and communities. For example, in the context of privilege and ableism, avoid implicit disability biases and inaccurate assumptions, such as everyone having stable internet connections, money to buy emergency supplies, a working vehicle, and the ability to walk, run, see, hear, speak, remember, and understand.

To strengthen mutual trust, transparent and honest assessments of weaknesses, strengths, and challenges are vital by supporting what needs to be said rather than what emergency managers want to hear. Advantages and payoffs from community partnerships include:

- Planning with people, not for people. Planning for the known needs of disaster-impacted people with disabilities means partners serving in specific and critical planning, response, and recovery capacity roles that decrease harm by protecting their health, safety, and independence during and after disasters and providing problem-solving, assistance, and resources.

- Strengthening compliance with civil rights laws by operationalizing physical, equipment, programmatic, and communication access.

- Developing processes, procedures, protocols, policies, and training with community partners, including disability partners (i.e., disability-led organizations and others with lived disability experience and knowledge related to disability, access, and functional needs issues).

Partnership models include disability emergency coordinating meetings consisting of cooperation, collaboration, communication, coordination, and problem-solving tasks to address unmet needs. (e.g., replacing left-behind, lost, or damaged consumable medical supplies and equipment such as wheelchairs, canes, walkers, shower chairs, hearing aids, food, medications, supplies, backup power, wheelchair-accessible transportation, understandable and usable communication, etc.). Following are a few examples of response and recovery coordination meetings put into practice:

- In 2007, Access to Readiness Coalition, The California Foundation for Independent Living Centers, and The Center for Disability Issues and the Health Professions at Western University of Health Sciences partnered to create an after-action report for the California wildfires.

- Starting in 2017, The Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies led weekly national stakeholder calls after Hurricane Harvey (Houston).

- In 2018 during and after Hurricane Florence, disability partners met in North Carolina.

- Since March 2019, the Florida Statewide Independent Living Council has gathered the Centers for Independent Living (CILs) for monthly and long-term planning meetings and conducts daily meetings during major disasters such as Ian 2022 and Idalia 2023.

- On February 28, 2020, The Partnership began hosting a daily COVID-19 disability rights and disasters call.

- In 2023, the disabilities-led Able South Carolina and South Carolina’s Centers for Independent Living led monthly meetings and daily meetings during major disasters such as Hurricane Idalia.

- On August 8, 2023, launched the Maui, Hawaii Wildfire Disability Task Force.

2. Community Partners

Community partners are not limited to Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD), which have emergency services as their primary mission. This reliance excludes many community connection helper networks that can serve critical supporting roles. Community partners refer to a broad group of potential partners, including:

- Businesses and business emergency operations councils often comprise businesses that conduct continuity planning and form partnerships with other businesses to support preparing for, responding to, and mitigating emergency risks;

- Health entities such as community clinics, health care coalitions, home health agencies, infusion centers, pharmacyservices (including mail-order plans), and vendors of consumable medical supplies, oxygen, durable medical equipment, pharmacy services;

- Big box stores;

- Logistics companies such as United Parcel Service (UPS), United States Postal Service, Federal Express (FedEx), Amazon, airdrop, and drone delivery;

- Private transit providers such as Uber, Lyft, rental car and airport shuttles, taxi services, and vehicles owned by community-based organizations;

- Personal assistance providers or caregivers (public and private);

- Lodging and housing providers such as Airbnbs, hotels, motels, building managers, and realtors;

- Utilities, including power and water;

- Community-based organizations focused on aging, disability, faith-based groups, family services, Meals on Wheels, schools (preschool, K-12, colleges, and universities), Cajun Navy, Trach-Mamas, CrowdSource Rescue, Crisis clean-up; and

- Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster.

Developing, maintaining, and sustaining the necessary emergency preparedness, response, and recovery capabilities require leadership and the coordinated efforts of partners from first responder disciplines, all levels of government, and nongovernmental entities. Going to community meetings can help other planners and responders discuss recruiting issues with community partners.

3. Working Sessions and Feedback

The old practice of conducting all working sessions through committees that convene in person monthly or quarterly is no longer practical. Neither are the one-way feedback methods for commenting on and reviewing the emergency operation plan (EOP), training content, documents, policies, etc., with minimal or no opportunities for discussion.

To maximize constructive feedback, use solution-based processes that ask challenging questions to identify service gaps and possible fixes. Sometimes, this can be accomplished through spontaneous meet-ups, texts, phone calls, emails, coffee lines, hallways, back of meeting rooms, receptions, etc. More often, it is with meetings tailored to the work that needs to be accomplished (email, small workgroups, virtual meetings, hybrid meetings). A combination of in-person and remote participation (i.e., hybrid or crowdsourcing) enables communication using virtual tools such as Zoom and Teams, which include those who have difficulty or cannot participate in person.

Crowdsourcing offers online opportunities to address specific challenges, solve problems, generate ideas, accomplish tasks, and provide subsets of members with tailored discussion forums. Crowdsourcing advantages include tapping into the collective wisdom and creativity of the experts and others with unique skills and perspectives to produce ideas and solutions, complete micro-tasks, conduct research, and minimize time-consuming commutes. With access to online materials via password, 24/7 access is available to minutes, documents, slide decks, upcoming events, etc.

Completing the feedback loop and building an accountability process is critical. Items that take significant time should stay on the agenda under “follow-up needed” or “pending items” until the issue is addressed. Building and sustaining community partnerships takes teamwork and multiple working sessions. This commitment means dedicating resources, staff, and backup staff, creating agreements, exercising and testing the details, and improving practices by applying new lessons.

4. Roles of Community Partners

It is important to overcome the no-additional-help-is-needed mentality of a government-centric approach to catastrophic disaster management and services. Building broad community partnerships involves developing and strengthening critical emergency capabilities and competencies, using lived and work experience skill sets, and delivering services rooted in understanding the details, diversity, nuances, and complexity of living with a disability. Given the known disaster resource constraints, these partnerships are “not nice to do, but a must-do.” The core value is recognizing that community partners can force multiply and amplify emergency management reach.

Community partnerships start with partners developing or having up-to-date continuity of operation plans (COOP). Partners must conduct an internal accurate assessment to determine if and what they can offer given their skills, capacities, and capabilities (staff, budgets, etc.). Examples of community partner roles include:

- Messaging – As a force multiplier, community partners can amplify messages, facilitate time-sensitive information dissemination to diverse communities, and continually test and improve their distribution methods. Existing influence and connections help reach disparate populations in complex media environments through customized distribution, multiple languages, and culturally appropriate methods. For example, some organizations that support people with intellectual disability are skilled at providing and reinforcing easy-to-understand messages using plain language, pictures, and repetition.

- Life-safety or wellness checks – Also known as welfare checks or safe-and-well checks, these checks consist of a phone call, text, email, or in-person visit to make sure individuals are safe and, when indicated, determine if they have any needs related to sheltering in place or evacuating. For the people these wellness checks may support, automated check-in systems can reach people through calls, texts, or emails and ask people to respond by indicating they are “ok” or “need help.” If there is no response, staff can reach out first to pre-identified higher-risk people, including those who are:

- Geographically isolated;

- Lack help from relatives, friends, and neighbors;

- Cannot use, understand, or be reached by alert and notification systems; or

- Transportation-dependent.

- Individual preparedness plans – Tasks to develop detailed emergency plans require time, skill, and often multiple meetings, which include:

- Helping people let go of denial and address scary, disturbing, and uncomfortable issues;

- Addressing details needed to shelter in place or evacuate;

- Labeling equipment with name, phone numbers, email address;

- Developing a helper list to identify, communicate with, and maintain support teams and support networks of people who agree to help when needed and check on each other in an emergency;

- Planning for power outages;

- Developing a communications plan to communicate with helpers in an emergency via landline phone, cell phone, text, email, or app;

- Signing up for local alerts and notifications that provide weather conditions and emergency information; and

- Collecting critical documents (paper and digital copies for a “grab and go” bag) that include:

- Helper contacts entered in cell phones and other devices;

- Hard copies of phone numbers, addresses, etc. when phone and digital resources are not available;

- List of essential equipment, serial numbers, date of delivery, and payers;

- Health insurance cards; and

- Medication lists and prescriptions

- Other roles can include:

- Evacuation assistance from structures;

- Transportation to and from affected areas;

- Personal assistant services (also called attendants and caregivers) who help with dressing, eating, grooming, toileting, transferring, shopping, or communicating;

- Assistance to divert and transition people from institutions;

- Sign language interpreting;

- Communication Access Real-Time Translation (CART);

- Mucking and gutting;

- Debris removal from accessible paths; and

- Telehealth services.

5. Agreements and Contracts

Sometimes there is a false expectation that all community partners will volunteer their time. The term “charitable organization” is misleading. A nonprofit tax status does not mean volunteers do all the work. Community-based organizations have contractual, financial, payroll, operating expenses, compliance, and deliverable obligations. Taking on emergency-related tasks means covering staff salaries, overtime, travel, etc., which is sometimes impossible without additional funding. Agreements must include the who, what, where, when, why, and how of reimbursement details in advance. Such details should include: mandatory participation in planning, drills, exercises, hot washes, and after-action reports.

Here are two examples of existing contracts with investor-owned utilities. In California, 211 centers and Disability Disaster Access and Resources, a program of the California Foundation for Independent Living Centers, have contracts to help people with access and functional needs, who live in high-fire-risk areas prepare for and cope with power outages. These services may offer help with developing individual emergency power plans, access to loaner backup battery systems, short-term housing support, accessible transportation, and home meal delivery.

6. Training

Old beliefs and practices that can hinder training efforts for community partners include in-person requirements, self-study courses, and hard-to-use training materials. In-person training can limit broad participation due to available space or minimal inclusion beyond government employees. Online self-study courses can seem vague, with unapplied theories for those lacking experience. Training notebooks, student manuals, and slide decks can be large and difficult to use for all partners.

Training teams and their managers using consistent training content is helpful for navigating competing priorities, heavy workloads, and a lack of manager support to convert lessons observed into practice and improve outcomes when identifying and applying new tactics and improving performance. Integrating content from government and community partners increases an understanding of different core values, cultural issues, specific terms, and jargon.

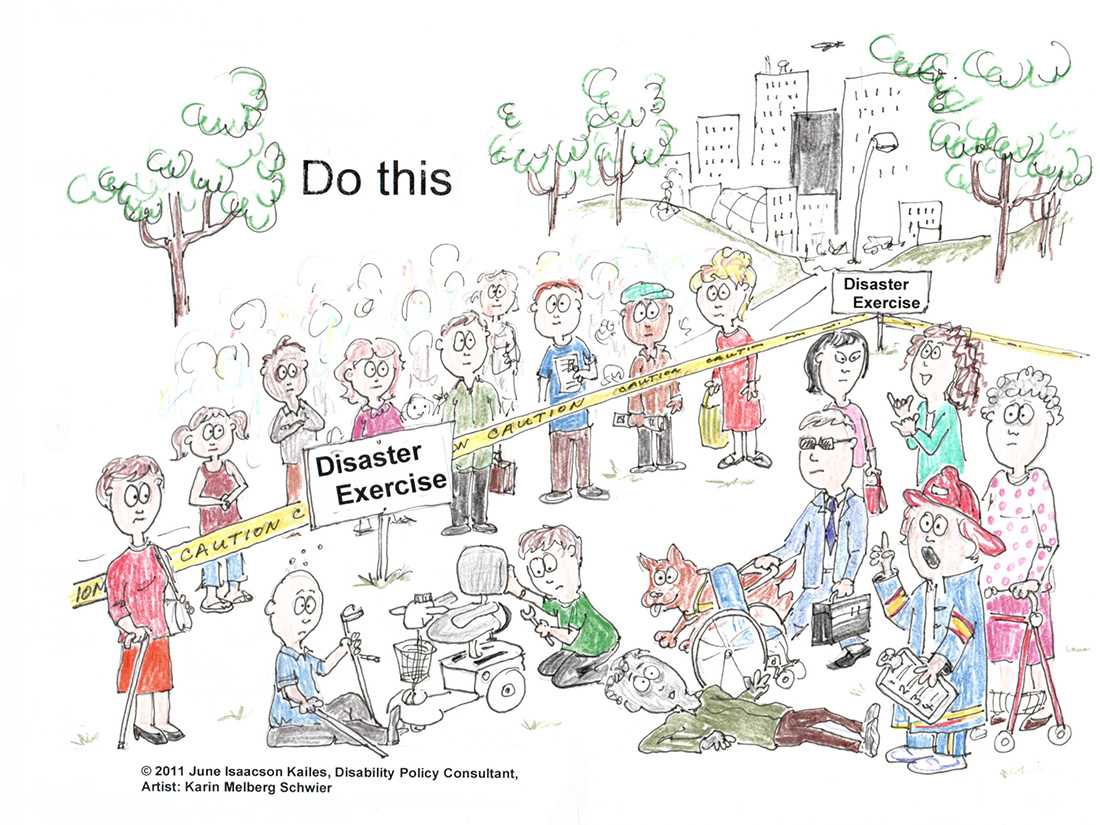

Just-in-time training can make lessons relevant, concrete, clear, and immediately applicable to discussions, plan development, and agreements. Drills and exercises that include community partners test and stress the system and promote stronger learning and greater impact through applied practice. When followed by honest assessments through hot washes and after-action reports, this training can result in changes in practice and policy.

Actionable, practical, tactical, and deployable steps through checklists, field operation guides, and job aides can sustain and reinforce competencies. Specific content easily accessed by the internet and mobile devices offers just-in-time opportunities for quick review when deployed. This tactic prevents deployed individuals from remembering, untangling, and connecting content from threads of information for critical roles from plans, processes, procedures, protocols, policies, and training notes.

7. Measuring Success

Traditional evaluation methods tend to focus on the process outputs and outcomes. Training evaluations, for instance, are often limited to feedback on the content and instructors coupled with the numerical statistics related to meetings held, speakers, training delivered, students in classes, and students who pass pre- and post-training tests.

A new way of thinking is to evaluate the impacts of those outputs and outcomes to help measure recovery as well as short- and long-term resiliency. In this discussion, outputs are things produced and activities that support the desired results. Outcomes are quantitative, measurable short-term effects and the results of outputs. The impacts are the broader, longer-term effects of the results. Following are a few examples:

- For just-in-time training, the outputs are the training developed and offered. The outcomes are the number of trainings delivered and the number of people completing the training. The impacts are easy-to-access short training rated as helpful and usable and reinforce the roles and responsibilities of deployed individuals.

- Regarding outputs of drills and exercises, the outcomes are the number of community partners participating, the number of participants honestly assessing drills and exercises in hot washes and after-action reports, and the number of emergency responses. Outcomes are also the number of lessons from these assessments applied through new or revised processes, procedures, protocols, policies, and training. The impact is when deployed partners apply roles and responsibilities in the field.

- For life-safety check interventions, the output is conducting the checks. The outcomes are the number of people who, as a result of these checks, receive needed food, water, supplies, or evacuation. The impact is that the interventions protect people’s health, safety, and independence.

- For individual emergency plans, the outputs are people who get help developing plans. The outcomes are the number of people with completed plans. The impact is that the implemented plans result in people being able to protect their health, safety, and independence.

The seven old beliefs and practices covered above must be re-evaluated and modernized using newer ones. As former Director of Homeland Security and Justice Issues William O. Jenkins Jr. testified in 2007, these tasks require continuing commitment and weighing “trade-offs because circumstances change, and we will never have the funds to do everything we might like to do.” Operationalizing teamwork with community partners fosters improved problem-solving and solutions to create, deliver, embed, and sustain real impacts, which are the objectives’ long-term goals and achievements.

Embedding competencies, capabilities, and capacities into multiple systems is iterative. This process involves identifying areas needing attention, setting priorities, evaluating progress, ongoing learning, continually improving, and sustaining the effort over many years. Those responsible for creating the sparks, the outputs, and the outcomes often do not get to experience sitting by the fire and enjoying the impacts.

______________________

Being at the table is not enough.

Don’t merely abide; lesser deeds will not turn the tide.

Avoid the vague, puffy, and fluffy.

Craft the actionable and the practical.

Build partnership capability and expand capacity wide, let impact be your guide.

Never settling for less, we strive for the best for ourselves and others on this lifelong quest.

— June Kailes (2024)

June Isaacson Kailes

June Kailes, a disability policy consultant (jik.com), has over four decades of experience as a writer, trainer, researcher, policy analyst, subject matter expert, mentor, and advocate. June focuses on building disability practice competencies and health care and emergency management capabilities. She uses actionable details, the “how, who, what, where, when, and why,” to operationalize the specificity needed to include people with disabilities and others with access and functional needs. June’s work converts laws, regulations, and guidance into tangible building blocks, tools, and procedures that close service gaps, prevent civil rights violations, and deliver inclusive, equally effective services.

- June Isaacson Kaileshttps://www.domprep.com/author/june-isaacson-kailes

- June Isaacson Kaileshttps://www.domprep.com/author/june-isaacson-kailes

- June Isaacson Kaileshttps://www.domprep.com/author/june-isaacson-kailes