- Articles, Emergency Management, Emergency Medical Services, Hospitals, Law Enforcement, Military, Public Health

- James Greenstone and Weldon Walles

Professional groups have debated and researched the best practices relating to the standards and quality of care sufficient to maintain minimum standards during a disaster. Due to the fluid nature of a disaster, it is difficult to abide by a standard that will fit every situation. For example, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic created an environment where an intense debate was necessary to examine best practices and standards in real time. Health care professionals and first responders often embrace the protocols associated with the standard of care that their professions demand. Shortcuts and inferior care are not generally acceptable.

Unlike health care professionals and first responders, the public does not seem to embrace the difference between normal circumstances and disasters, at least where resources are concerned. The public demands a high standard of care even when resources are exhausted. They may not be aware of how legal restrictions, politics, and logistics affect the level of care in disaster conditions. Expecting a high standard of care under adverse or impossible conditions places pressure and stress on health care workers and first responders, affecting their mission. When they cannot achieve the impossible, the fear of litigation and liability exposure may distract them to the point that it affects their decision-making abilities to the detriment of their patients.

Making decisions that enhance the survivability of one person over another increases the mental strain on responders, especially when resources are dwindling.

Emergency response agencies train personnel on how to perform tasks and how to use tools and resources. However, they may not always prepare for the psychological challenges they could face. With the isolation and sensory deprivation that astronauts face when deployed into space, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has assessed psychological risks through many experiments over the years to prepare its astronauts. For example, in 1967, it used isolation chambers for up to 10 days to observe changes in participants’ cognitive and other functional abilities. A participant from a 2013 NASA experiment, where six people were isolated in a geodesic dome for four months to simulate life on Mars, compared lessons learned from that experience to the skills needed during the COVID-19 isolation period. Although a bit extreme, these NASA experiments show that shorter sensory deprivation periods can simulate the long-term deprivation astronauts will encounter later.

Introducing a New Training Concept

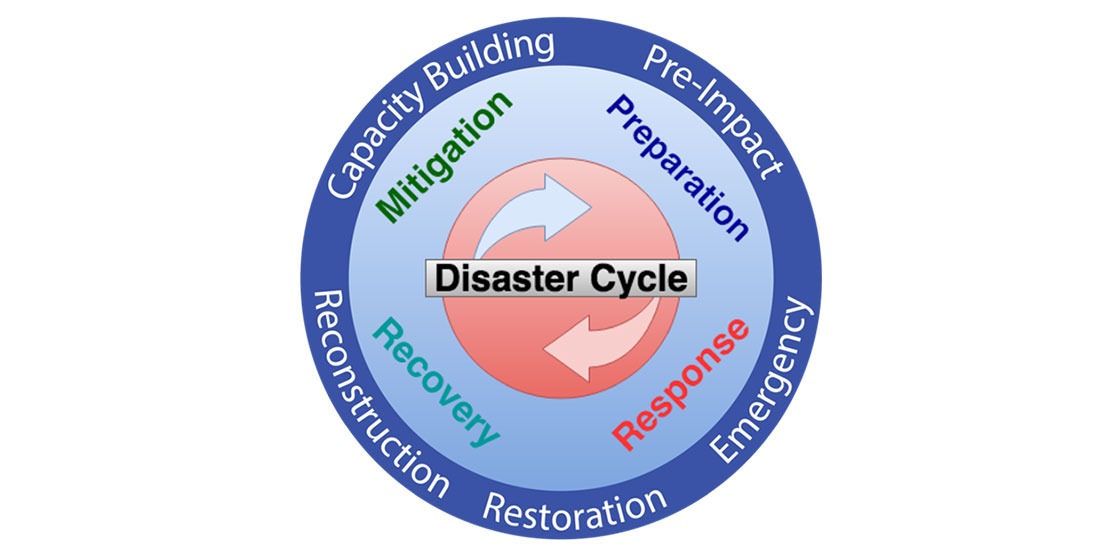

Mass casualty, disaster incidents, and similar events that occur without warning can create situations that cause health care professionals to deviate from known and practical protocols, thus leaving them to invent or utilize alternate responses. When health care workers and resources are overwhelmed by the sheer number of victims, lack of supplies, or inaccessibility of terrain, responders must allocate resources to those who will benefit most.

Also, the responder’s decision-making process must be sufficient to use the available resources on the greatest number of survivors who can benefit the most from those resources. Perhaps the most significant pressure on the responder is the realization that it is not possible to help every victim. Health care workers and first responders are dedicated individuals who risk their lives responding to and transiting disaster scenes. However, having to gauge the survival potential of each victim and make decisions that enhance the survivability of one person over another increases their mental strain when the reality of dwindling resources becomes apparent.

To address modern response concerns, the Greenstone-Walles Sufficiency Testing and Training offers a simple guide to help mentally prepare disaster responders for the worst. Using a simple task unrelated to a specific disaster scenario, participants complete an examination of their approaches to limited resource availability. This examination, coupled with understanding the expectations they can derive through simple tasks, helps them acknowledge that they can do only so much with their resources. Understanding expectations may enhance their overall performance and let them know that the agency they are working for will give their full support. Items to consider before beginning a new training include:

- It is detrimental to convey to the planning team or participants that no training can replicate the actual situation, no matter how sophisticated. For example, many lessons learned from COVID-19 show that health care workers would have benefited from more crisis standards of care training before responding to the pandemic.

- Disaster scenarios are less than ideal circumstances. However, these may be the norm in certain circumstances.

- Responders must understand their limitations and realize that, with time as a determining factor, some dire situations have no practical solutions. In bad scenarios, guilt can lead to hesitation and derail triage decisions (e.g., deviations from protocols, falsely believing that the responder is expected to do the impossible). Guilt triggers a self-preservation mechanism, where the person coping with the guilt blames another for asking them to do something impossible.

- When comparing one’s mind to a mechanical device, guilt is like a foreign object dropped into a gearbox. It can bounce around at first and not cause too much of a problem, depending on how well-engineered the machine/mind is. But if that foreign object/guilt settles in one place, it can cause a range of problems up to and including catastrophic failure.

There will be times when responders are in a no-win scenario. The best action is to follow established protocols as closely as possible, which is especially important for two reasons when attempting to help someone fails:

- Following established protocols limit liability.

- Following the steps in the protocol provides an outline when filling out after-action reports.

For this topic, failure simply means a lack of a successful outcome, which is subjective. Failure is often stigmatized as bad, but it usually means an expected result was not achieved. Many failures may lead to learning what can be done to thwart future failure.

Exploring the Training Process

NASA recognized that it is critical to mentally prepare astronauts for the unfamiliar conditions they would face when traveling into space. Similarly, those who respond to disasters must be equally prepared – physically and mentally – for their jobs under adverse circumstances. As such, this article proposes a new type of training where a failure scenario prepares responders mentally for more significant situations.

Target participants for the Greenstone-Walles Sufficiency Testing and Training are persons who are likely to be deployed. Instructors ask them to complete simple tasks without providing them with the necessary items to complete the task. The goal of this experimental exercise is for participants to realize that they should not blame themselves for not completing any small or large task under adverse conditions. Instead, they must accept that they can only do so much given the details of a specific situation.

If this or a series of similar exercises were used at the beginning of a training, it would instill in the participants that some tasks are impossible and that the responder is not to blame if they did all they could with what they had available at the time. The emphasis must be on rendering the best services possible under the existing conditions to the most who can benefit from those services under the current circumstances.

Training and discussions could also occur virtually (e.g., via Zoom). Assign each person to a breakout room. Give them their individual instructions and time limit. The moderator/trainer then goes to each breakout room and does the discussion questions. These breakouts could be accomplished with multiple people, one or two leaders, a 30-minute time limit, and individual discussions and evaluations. Each participant would need to bring a sheet of white paper only. Leave all else and writing instruments out of breakout rooms.

Sample Exercise

Provide each participant with a piece of paper and ask them to draw a black-and-white landscape scene. The only item each has to complete the task is a piece of paper. They have no pencils, pens, or other drawing instruments, have 30 minutes to complete the task in isolation, and cannot ask questions. The moderator or anyone else does not communicate with them once the door to their isolation area is closed.

The moderator/trainer returns 30 minutes later to see what happened, what the participants did or did not do, and how frustrated they are with the assigned task. Then the moderator/trainer gives them a questionnaire with the following questions (no permanent record should be kept of their responses to the moderator/trainer’s questions or discussion content):

- Were you able to complete the task? Unless the participant cheated and used a pencil they had hidden or some object they were not given to complete the task, the answer will be “no.” In other words, they did something to deviate from the accepted protocol.

- This part of the simulation attaches liability when there is a deviation from accepted protocols, no matter how good the intentions or the desire to succeed.

- If not, why not?

- What could you have changed about yourself to do better?

- What items would you have needed to complete the task?

- Who do you think, if anyone, is to blame for your failure?

- If you were deployed during a disaster and the necessary equipment was unavailable to save someone, would you blame yourself if you could not save them or provide the proper equipment or services?

- What lesson did you learn from this exercise?

Encourage the participants to explore their feelings and perspectives on these issues deeply. After completing the questionnaire, additional post-testing questions for further discussion could include:

- What did you initially think about the task you were asked to do during this exercise?

- Did you believe this was an impossible task?

- Did you continue to think of ways to complete the task?

- Did you think others may figure out a way to complete the task, and you may not?

- How did this exercise affect your anxiety?

- What emotional response did you feel about your failure to complete the task?

- Did you place blame on anyone other than yourself for not completing your task?

At the end of the session, provide each trainee with a copy of the paper Crisis Standards of Care – A Disaster Mental Health Perspective.

Final Thoughts and Conclusion

In many cases, relatively simple exercises in a non-disaster setting could help responders deal with disaster-experienced feelings, especially when they must depart from their usual and required standards of patient care. The more severe NASA experiments show that preparation in a controlled environment can reap big rewards in the actual environment. Training can help prepare those who eventually find themselves in the real or anticipated scenario. The proposed Greenstone-Walles Sufficiency Testing and Training is simple, whereas NASA’s is complicated. However, both prepare responders for alternate standards of care thinking without the guilt and trepidation cited earlier.

No matter the situation, the needs often outnumber the resources available at disaster scenes. It comes down to simple math. The resources must be prioritized to reach the neediest first, with a significant likelihood of survivability. Good intentions and best efforts only go so far. The reality is that some victims will suffer due to a lack of critical resources. The health care worker and first responders must make decisions based on their training and experience and resist the guilt associated with making decisions that can adversely affect lives.

Experienced health care workers and first responders who have been on-scene in disasters and situations under normal conditions can compare the two experiences and understand their differences. Knowing these differences helps them adjust to their roles more quickly in a particular scenario. The way to acquire this knowledge is through experience. This training includes practical exercises designed to teach practitioners that the limitations of their ability to help are directly proportional to the number of resources at their disposal. These simple exercises presented here are designed to approach that spectrum.

Additional Help and Resources – In the Field or Out

- SAMHSA Disaster Distress Helpline – Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) offers 24/7 crisis counseling for those experiencing emotional distress related to natural or human-caused disasters; call or text 1-800-985-5990; text “TalkWithUs” to 66746; en español.

- SAMHSA Behavioral Health Disaster Response Mobile App – SAMHSA offers multiple resources in its Disaster Mobile App, including a directory of behavioral health service providers in areas affected by disasters.

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (formerly known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) – This 24/7 national network of crisis centers provides free and confidential crisis support to help prevent suicides; text 988; call 1-800-273-8255; for TTY, dial 711, then 988; for deaf/hard of hearing/American Sign Language users, call or text 1-800-985-5990; Veterans, text 838255; en español, 1-888-628-9454.

Additional Readings for Psychological Risk Preparedness

- How to Prepare for the Worst Without Being a Pessimist

- Mind Over Disaster: Mentally Preparing for the Worst

- National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care

Disclaimer: The material and the exercises presented or suggested herein are experimental and for general informational purposes only. This material does not attempt to provide counseling services or other therapeutic services or medical advice. Please consult with a qualified and licensed medical or mental health professional for specific concerns, personal or otherwise.

James Greenstone

Dr. James L. Greenstone (Ed.D., J.D.) is a psychotherapist and a Supervisory Mental Health Specialist with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Disaster Medical Assistance Team. Formerly, he served as Director of Psychological Services for the Fort Worth, Texas Police Department. Dr. Greenstone is the author of The Elements of Disaster Psychology: Managing Psychosocial Trauma; The Elements of Crisis Intervention, Third Edition; and Emotional First Aid: Field Guide to Crisis Intervention and Psychological Survival. Also, he was a collaborating investigator for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM 5) published by the American Psychiatric Association. Dr. Greenstone is currently a Professor of Disaster and Emergency Management at Nova Southeastern University, Kiran C. Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine. Recently, Dr. Greenstone was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress. Additionally, he is also a member of the Tarrant County Medical Society Ethics Consortium. Dr. Greenstone may be reached at dr.james.greenstone@gmail.com

- James Greenstonehttps://www.domprep.com/author/james-greenstone

- James Greenstonehttps://www.domprep.com/author/james-greenstone

- James Greenstonehttps://www.domprep.com/author/james-greenstone

Weldon Walles

Weldon Walles, FWPD (Ret.), is a crime scene analyst and a retired Fort Worth Texas Police Department (FWPD) Officer. He is a co-author of “The Courage to Commit: A Guide to De-escalating the Crisis of Citizen-Police Relations.”

- Weldon Walleshttps://www.domprep.com/author/weldon-walles